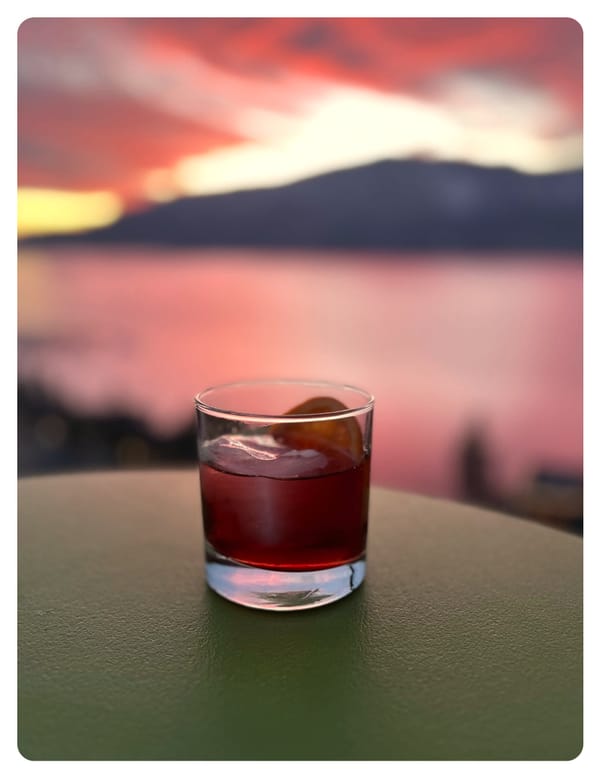

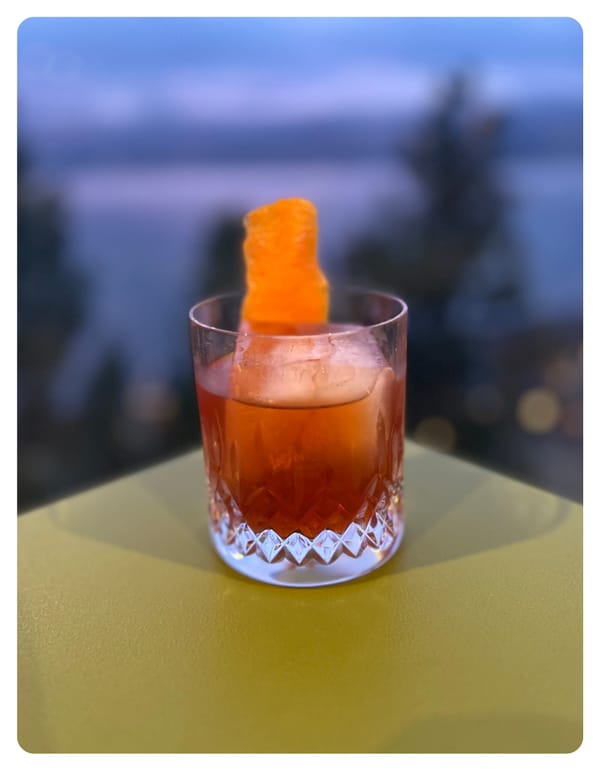

Black River No. 1

- 2 oz Appleton Rum

- ½ oz Amaro Averna

- 1⁄2 oz Kahlúa

- 1 dash Orange bitters

- Stir ingredients in ice for 20-30 seconds, strain over a large rock of ice in an Old Fashioned glass

- Garnish with an orange twist.

Happy Friday, friends. How was your first full week back at work after the holidays?

This week’s cocktail is likely the first of many drawn from a single, prolific source. I’ve been sitting on this particular entry for a few weeks now, but to understand why, a bit of context is required.

About a year ago, one of my favorite YouTube bartenders, Anders Erickson, featured a cocktail called the Wardroom. In that video, he spoke about a group of drinks listed on Difford’s Guide—one of my most trusted cocktail references thanks to its depth and crowd-sourced rigor—that are attributed to a single creator: J. E. Clapham. The name stuck with me, though at the time I was deep in the practical and emotional work of relocating to Canada, so the thread went unexplored.

Fast-forward to a couple of months ago. While researching cocktails to potentially feature here, another recipe surfaced with the same attribution: J. E. Clapham. Memory triggered. I pulled on the thread again and discovered that Difford’s list of Clapham-authored cocktails is not just long—it’s impressively systematic. Even more compelling, his stated approach mirrors my own: using established cocktail archetypes as frameworks, then adjusting proportions and modifiers to discover new palate experiences. As a professionally curious person, I couldn’t leave it there.

From the digital trail available, Clapham appears to embody the maxim that we all contain multitudes. He is an English literature professor at Oxford and, simultaneously, a deeply methodical cocktail creator with an academic approach to knowledge management. Whether he bartends professionally remains unclear—those details don’t always surface on LinkedIn—but what is clear is the scope of his work.

Through extensive personal research, travel documentation, and historical sourcing, Clapham has built a substantial private database of cocktails: classics, variations, and original creations. Many of these have been distilled into a series of compact, affordably priced cocktail books, each organized around a single modifier spirit.

Notable titles include:

- Beyond Compare: A Campari Cocktail Book

- The Chartreuse Cocktail Book (Volumes 1 and 2)

- The Suze Cocktail Book

- The Bénédictine Cocktail Book

- Brancaphile: A Fernet-Branca Cocktail Book

- The Dubonnet Cocktail Book

- The Cynar Cocktail Book

- The Smith & Cross Cocktail Book: How to Mix the Ultimate Jamaican Rum

The Black River No. 1 comes from another of these volumes—That’s Amaro: An Amaro Cocktail Book—which I was fortunate enough to receive as a Christmas gift this year.

As I’ve mentioned before, cocktails became a serious interest of mine during the pandemic. A confluence of isolation, curiosity, and an already-maturing global cocktail renaissance pulled me in. In Portland, that renaissance had local champions like Jeffrey Morgenthaler, whom I’ve referenced here previously. What distinguished this modern era from earlier cocktail booms was a broader embrace of bitterness—specifically, the rediscovery of spirits that could contribute both sweetness and bitterness in a single ingredient.

Amaros.

Derived from the Italian word for “bitter,” amaro is a broad category encompassing liqueurs made from neutral spirit infused with roots, herbs, barks, citrus peels, and spices. Traditionally consumed as digestifs, their vegetal, bittersweet profiles were once considered niche or old-fashioned. In the context of modern cocktails, however, amaros have proven uniquely effective at creating balance and complexity. When we renovated our basement just before COVID lockdowns began, I organized my bar shelves accordingly: whiskey on one side, amaros on the other.

You can imagine, then, my excitement at discovering Clapham’s work—both for its structure and for its philosophical alignment with how I think about drinks.

This first selection, the Black River No. 1, does not disappoint. Since launching Flavor Notes, I’ve found myself increasingly drawn to Old Fashioned–style cocktails built on rum rather than rye or bourbon, and this is a standout example.

The backbone is a generous two-ounce pour of Appleton Estate rum. The more aged the expression, the better—the additional barrel influence adds depth and warmth. Supporting it is a restrained measure of Amaro Averna. Known to many as the vermouth substitute in a Black Manhattan, Averna is a relatively approachable amaro, offering bittersweet notes of herbs, citrus, and baking spice. On the amaro spectrum, it sits comfortably between the assertive intensity of Fernet-Branca and the lighter, floral sweetness of Amaro Nonino.

Averna acts as a bridge to the third ingredient: Kahlúa. Its coffee character is present but controlled, contributing as much caramelized sweetness as roasted bitterness. As perhaps the most recognizable coffee liqueur, Kahlúa remains the default choice for drinks like the White Russian—forever immortalized in The Big Lebowski.

A single dash of orange bitters ties everything together. Sweetened coffee and orange have a long history as complementary flavors, something I first internalized years ago at Jim & Patty’s Coffee on NE Fremont Street in Portland, where their Café Borgia—a latte served with an orange wedge—made the case decisively.

The expressed orange twist leads on the nose, easing you into the coffee aromatics beneath. On the palate, the Jamaican funk of the rum meets Averna’s spice and Kahlúa’s coffee at the outset, briefly forming a cola-like impression that leans into the drink’s coffee lineage. Citrus and bitterness then carry the drink across the mid-palate, before fading into lingering coffee notes and the warming proof of the rum.

As you browse for your next cocktail book and debate your favorite modifier—a difficult decision, I know—the Black River No. 1 makes an ideal winter companion: contemplative, balanced, and quietly grounding in increasingly unsteady times.

Like many of you, I woke last weekend to news that severe political actions had once again altered the lives of ordinary Venezuelans—and that the United States appears to have learned little from past attempts to secure the world’s oil reserves through coercive means.

Rather than speculate about what the U.S. has done or may do next, I want to use this space to outline Canada’s energy profile, the role oil plays within it, and the steps Canada and its provinces are taking to diversify oil exports beyond the United States.

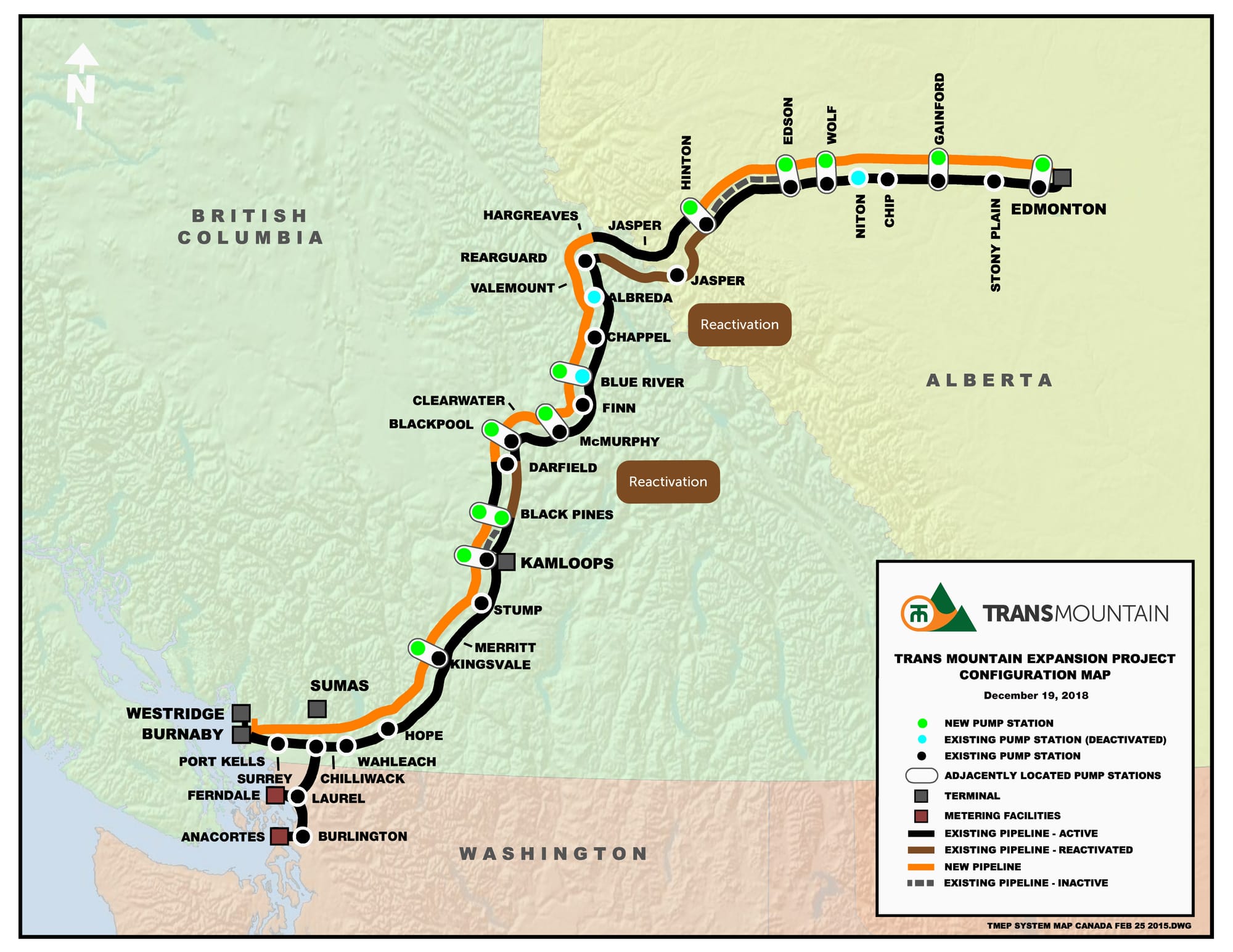

Canada sits atop one of the world’s most significant energy endowments. It holds more than 160 billion barrels of proven oil reserves—primarily in Alberta’s oil sands—ranking fourth globally and first among major free‑market democracies. Canadian crude production in recent years has exceeded 5 million barrels per day, complemented by substantial output of natural gas, hydroelectric power, uranium, and coal (the latter exported mainly to Asian markets). Together, these resources make Canada a major net energy exporter and a strategically important player in global energy security.

Historically, however, Canada’s energy exports have been overwhelmingly tied to the United States. Roughly 90% of Canadian crude oil exports and nearly all natural gas exports flow south like a black river via one of the world’s most integrated bilateral pipeline systems. While this integration has delivered stability and revenue, it also creates vulnerability—something underscored by recent U.S. tariff threats and increasingly unpredictable trade rhetoric.

Diversifying export markets matters now for several reasons:

- Reducing geopolitical risk by limiting dependence on a single buyer.

- Accessing global pricing through Asian and European markets.

- Supporting long-term economic resilience as global demand evolves under electrification and climate policy pressures.

Canada has already taken concrete steps in this direction. The most significant is the Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX), which became fully operational in 2024. By tripling pipeline capacity to the Pacific Coast, TMX enabled Canadian crude to reach global markets at a meaningful scale. Non‑U.S. oil exports have more than doubled since its completion, with China emerging as a leading buyer via this route. Prime Minister Carney will be in China next week, in fact, to nurture and expand the relationship between Canada and China.

Beyond pipelines, federal and provincial governments are exploring partnerships with foreign refiners—particularly in Japan—to co-invest in capacity capable of processing Canada’s heavy crude. Ottawa has also articulated a longer-term goal of doubling non‑U.S. exports over the coming decade, alongside broader trade diversification with partners such as India and China.

At the same time, Canada continues to advance renewable energy and emissions-reduction policies. The country targets a carbon‑neutral electricity grid by 2035 and net‑zero emissions by 2050, supported by carbon pricing, clean power incentives, and provincial programs promoting wind, solar, hydro, and electrification. Provinces like Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia have been especially active in this transition. Our own home in Kelowna—only five years old—reflects these policies, with rooftop solar and pre‑wiring for EV charging already in place.

Canada now stands at a crossroads. Its vast resources and stable governance position it as both a reliable global energy supplier and a credible partner in the energy transition. Diversifying markets is not simply an economic calculation—it is a matter of sovereignty, resilience, and long‑term national strategy.

Whether with elbows up, or with one arm down holding a Black River No. 1, I toast the future we shape for ourselves—one protest, one relocation, one job application, or one carefully stirred cocktail at a time. Cheers. 🍁🛢️🌞🥃

RIP Renee Nicole Good. Gone but not forgotten.